Signals and Systems

Introduction to Signals and Systems

Why am I here?

First of all, why on earth are you taking this course? That's the question my professors

never seemed quite able to answer with anything other than "it's important". In a sentence,

this class is gonig to teach you how real-world "systems" (be that the leaves on a fern,

a pool of water, a tuning fork, an electrical circuit, a car, a plane, a bookshelf - yes,

I am serious!) respond to outside influences (like a kick), and how we can represent those outside

influences and their responses with "signals".

It will teach you universal characteristics

of all these systems, along with the framework to analyze them. The framework you will learn is used by

Control Theory to not only analyze real-world systems, but

make them do our bidding. You will also learn Fourier Analysis, which is probably the most powerful

tool in the electrical engineer's arsenal. It allows any of the systems mentioned above

and how they respond to the outside world to be represented by a single graph, called the Transfer Function (more on that later), which you, as an engineer, can look at and immediately recognize important characteristics of. Imagine that. Being able to represent an airplane and how it responds to the world in a single plot, which you can look at and analyze, often in a couple of seconds. That just seems like cheating.

And, in fact, it is. In this course, we are making the simplification that everything is "linear"

and "time invariant", properties which we will learn more about in the future.

In reality, no system is perfectly linear and time-invariant (known by the cute acronym LTI).

Fortunately, and somewhat surprisingly, this turns out not to be a huge

problem, especially for electrical engineers. You will find that most of your work as an EE is working

hard to ensure the systems you build do behave as "LTI" systems, and for the most part,

you will be able to directly use the tools you learn in this class without modification. I do all the

time. I hope you will find that signals and systems is not just a useful, but also

a beautiful subject worthy of your study. I can tell you it has profoundly changed how I see the

world in the years since I have taken it, and it has never stopped being critically important.

Course Overview

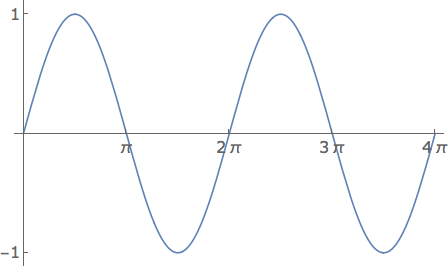

At the heart of signals and systems is the first "signal" we will meet, the humble sinewave.

We will first spend a few lectures reviewing

the sinewave, along with the concepts of frequency, phase, shifting and scaling. Basically, we want

to be able to play with this sinewave, squish it from any direction, make it go faster or slower,

or shift it up and down, left and right. It's pretty straightforward stuff, but the math can

be non-intuitive and easy to get lost in, and there's some important definitions along the way

that we will be using throughout the course.

Immediately after getting better-aquainted with the sinewave, we are ready to meet our first "system",

the damped pendulum. Or, if you prefer, your best friend on a swing. They both use the same math (so

long as your friend doesn't wiggle too much!). We will see something interesting about this "system" -

if the driving force ("signal") I am applying to it is a sinewave, the movement of the pendulum is also always

a sinewave, regardless of the properties of that pendulum. The sinewave will be scaled and shifted,

but it will always always stay a sinewave with the same period (see why we just reviewed scaling and

shifting of sinewaves?). This, we will find, is true in general of most linear systems, and this is

what makes them spectacularly easy to analyze.

But we will find, even for this simple example, that the sinewave by itself is just a little inconvenient.

Dealing with it requires handling trigonometry, remembering trig identities, bleh. Not a fan.

Fortunately, there is something that makes all the math easy as pie - the complex exponential.

Derivatives turn into multiplication, and trig identities melt away into simple addition. If we use the

complex exponential, and just add two of them together at the end, we can do the same exact problem

blazingly fast. We will review complex arithmetic and complex numbers for those who haven't met

them before.

This is all fine and good, but where are we going to find sinewaves (not to mention complex exponentials!)

in the real world? Isn't everything more complicated than that? Well, no, it turns out. Bizarrely, we

will find that any periodic (repeats itself in time) signal can be represented by a sum of appropriately scaled and shifted

sinewaves of different frequencies. This is called the Fourier Series.

Because of the properties of linearity and time-invariance (which

we will define and discuss here), since the response of a system to a sinewave is just a scaled and

shifted version of the same sinewave, we can "decompose" the signal we feed into our system into

a bunch of sinewaves, feed those in to the system, figure out what they look like after they go through

the system, and add all those up! This is what's known as a system's "Transfer Function", and this

will be ubiquitous in electrical engineering and physics. If you're concerned of getting lost

at this point, don't worry. We will work through some examples.

Again, it's cool and all that this works for periodic signals, but I haven't recently met any

signals that stretch from \( - \infty \) to \(+ \infty \) and repeat themselves over and over again.

That's just a silly amount of unrealistic. Fortunately, through the mathematical wizardry that is

the limit, we can imagine 'stretching' the period of our signal until it becomes infinite. In this

case, the sum will turn into an integral, and the Fourier Series becomes what is known as the

Fourier Transform, which we can use to represent any signal, and the response of any

linear and time-invariant system.

Next, we take a brief detour to meet a concept that will prove obscenely

powerful in subsequent courses: filtering. This is basically re-interpreting the transfer function

as something we can use for our own ends. Imagine we want to smooth out a signal, or it has

a slowly-varying offset that we want to get rid of? Filtering can do this for us.

We will also meet a concept central in communications, circuits, signal processing, and lots of

other disciplines too: modulation. Together, filtering and modulation will help give us an

intuitive feel for what the transfer function actually is and how to interpret it and use it.

Up to this point we have only been dealing with sinewaves and exponentials, but they turn

out to not be the only useful signals around. We will meet another, the impulse, which is extremely

useful, and closely related to the transfer function. The impulse has a physical interpretation

(imagine hitting something very quickly with a hammer), and the response of a system to an impulse

(which is called, quite creatively, the system's "impulse response"), will tell us how our system

responds to sudden kicks or bursts of energy. This, along with the transfer function and Fourier Transform,

are the most important concepts in this class. We will see, through the Fourier Transform, how

feeding in an impulse to our system allows us to infer the transfer function. This is actually how

most simulators you will use in your career work.

But the impulse response is useful on its own too! It turns out (again, this is really weird), that

just as any signal could be decomposed into sinewaves, any signal can be decomposed into impulses. Then,

if we can figure out the response of our system to one of those impulse (just scale the impulse response)

we can figure out how it response to any sum of scaled and delayed impulses. This is what is known

as the convolution integral, or simply, convolution. Perhaps not surprisingly given the frequent

occurence of coincidences in this course, it turns out to be deeply connected to the Fourier Transform.

Up until this point we have been discussing what is called "continuous-time" signals and systems. That

simply means that time is treated as a continous variable, and we deal with the "signals" (or functions)

that we know and love. However, not all signals are continous. Anything represented on a computer, for

example, is discrete. Information from the outside world is only collected every so often in brief packets.

This process is called "sampling". We introduce the math behind sampling, and (if you aren't immune to

surprises by now, get ready), how we can prevent information from being lost in the process of sampling.

This is known as interpolation, and the underlying theorem known as Nyquist's Theorem.

Now that we have sampled our signals, how do we represent them? We will discuss how to do this using

the discrete-time index n (as opposed to t).

We will re-introduce the sinewave, complex

exponential, and impulse in what is called "discrete time". They are pretty much the same, but with some

added twists on how fast a sinewave you can represent.

Just as you can filter and modulate signals

in continous-time, you can do this in discrete time as well. We will discuss how to create such filters,

and figure out how to translate back and forth from continous-time filters and modulation to discrete-time.

This is spectacularly useful, because a filter in discrete time is just a couple lines of code, whereas

in continous time it typically uses resistors, capacitors, inductors, and opamps (which cost money!).

Finally, we will learn a couple of useful tools that go beyond the Fourier Transform, and are very useful subsequently in control systems - The Laplace Transform, and it's cousin in discrete time, the Z-Transform. What's next after this course? Moving on to Control Systems, or, for an elective, Fourier Optics, which extends what you learned about 1D signals and systems into two dimensions.

If you found this content helpful, it would mean a lot to me if you would support me on Patreon. Help keep this content ad-free, get access to my Discord server, exclusive content, and receive my personal thanks for as little as $2. :)

Become a Patron!